The grants to Martin Hallbeck, Per Hammarström and the other researchers were announced at a ceremony arranged by Hjärnfonden. Photo credit HjärnfondenThere was fierce competition for research grants from the special call put out by the Swedish Brain Foundation for Alzheimer research. Only six of the 113 applications were successful. Two of the researchers who receive grants for their research projects are at Linköping University, in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and the Faculty of Science and Engineering.

“The research grant from the Swedish Brain Foundation is recognition of the quality of research at Linköping University within neurodegenerative diseases, where we collaborate across discipline boundaries. Good things happen when scientists from different disciplines, such as medicine and chemistry, meet”, says Per Hammarström, professor in protein chemistry at the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology, and recipient of SEK 6 million spread over three years.

Damaging protein with many forms

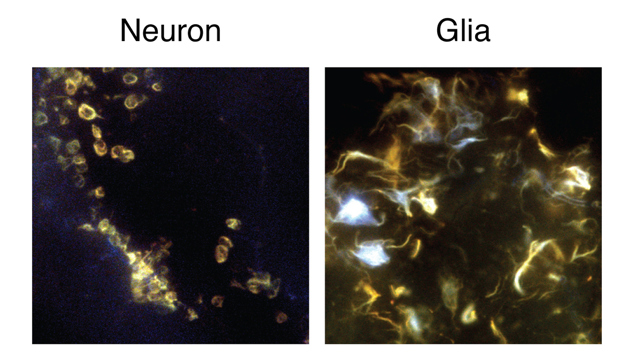

New treatment methods and better diagnosis that can discover Alzheimer disease at an earlier stage are two important objectives for the researchers, independently of the field in which they work. In Alzheimer disease, nerve cells die as a consequence of proteins forming aggregates and damaging the cells. The aggregates, also known as “plaques”, consist mainly of two proteins: amyloid beta and tau. Much previous research has suggested that misfolded forms of amyloid beta initiate the processes that lead to Alzheimer disease, but many questions remain about how this happens. For example, older people often have senile plaques in their brain, but many of them never develop symptoms. Others may have few plaques, but even so fall ill. Why is it that not everyone with plaques experiences symptoms? Why do some people become more sick than others with small amounts of plaque, and why is the progress of Alzheimer disease significantly more rapid in some people than in others?Per Hammarström. Photo credit IFM, Linkoping University

Per Hammarström believes that the answers to several of these questions are related to the properties of amyloid beta. He has studied the misfolded proteins in Alzheimer disease for a long time, and shown that they do not take up a single form, but many. Even in a single patient, and in a single plaque, several different forms of misfolded proteins can be present.

“As a chemist, I’m interested in how differences in the molecular structure of the proteins cause clinical differences. We can speculate that certain forms of amyloid beta are more toxic than others, such that a smaller amount is needed to give rise to the disease. One important question is which forms of the misfolded protein we should direct future treatments and diagnostic tools against”, says Per Hammarström.

The final goal for Per Hammarström and his colleagues is patient-specific diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease. In order to achieve this, they must understand the different forms of amyloid beta and how the variation is linked to disease differences.

“The strength of our research project is that we have tracer molecules that recognise different forms. The tracer molecules have been created here at LiU by scientists in organic chemistry in the division, and are an incredibly important component. We can use the tracer molecules in laboratory experiments, in various model systems such as fruit flies, and in tissue samples from humans. The research grant from the Swedish Brain Foundation means that we can bring to reality many of the ideas whose time, we believe, has come”, says Sofie Nyström, docent in the research group.

Halting the spread?

The second LiU researcher to receive funding is Martin Hallbeck, associate professor in the Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine and consultant in clinical pathology at Linköping University Hospital, who receives SEK 3 million over three years. His research looks at how the disease spreads and affects increasing parts of the brain. How does the disease spread, and why is the progression more aggressive in some patients than in others?

Martin Hallbeck and his colleagues have recently discovered two different mechanisms by which toxic protein aggregates can spread between cells. The next question is whether it is possible to influence these mechanisms, and in this way brake the spread of the disease. The scientists will also investigate different ways to measure the presence of harmful proteins, with the goal of developing diagnostic tools that are more sensitive than those currently used.Martin Hallbeck Photo credit Emma Busk Winquist

“We will not only continue to work with investigating the mechanisms by which Alzheimer disease kills nerve cells and spreads to new parts of the brain, but also attempt to increase our knowledge, to bring future treatments and diagnosis. The opportunity to collaborate with other researchers at Linköping University in neurodegenerative diseases is important for this”, says Martin Hallbeck.

He emphasises that the money collected by organisations such as the Swedish Brain Foundation plays an important role in research funding.

“Of course, it’s extremely gratifying and stimulating to receive recognition for our work. The grant means that we can carry out research projects more rapidly, and contribute more to increasing our knowledge of Alzheimer disease. We rely totally on research grants from funding bodies such as the Swedish Brain Foundation for our research and the ability to help patients in the future”, says Martin Hallbeck.